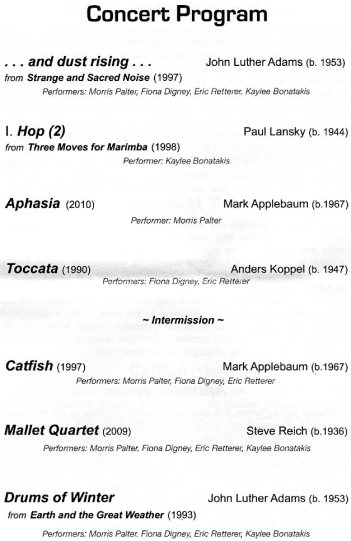

Dr. Morris Palter, graduate of the University of Toronto School of Music, disciple of Steven Schick and currently Assistant Professor of Music at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks flew into Toronto with 3 of his graduate students and presented a concert of music for percussion at the Music Gallery Monday night, 7th of May.

I’m not a great fan of music by John Luther Adams (b.1953), but he’s hot now and I suppose I should be happy for him. He has labored in the wilderness, literally, for many years and besides, is a good guy. Years ago I visited him in his rustic, but comfortable cabin in the Bush outside Fairbanks. There are no doubts in my mind about his dedication and honest approach to his music.

Adams’. . . and dust rising . . . (1997), a work for four snare drums, needed better orchestration. Morris’ group had little choice here. All the instruments were rented from a local shop and in such cases, one must accept what’s delivered. To my ears, the piece was no more than an exercise in counting. It pales in comparison to James Tenny’s (1935-2006) Crystal Canon from Three Pieces for Drum Quartet (1974).

The hit of the show for me was Aphasia (2010) by Mark Applebaum (b.1967). It was performed by Dr. Palter, who from past experience seems to thrive on and enlarge theater pieces. I cannot imagine a better performance of Aphasia. I was enchanted from beginning to end.

The audience was small and as usual, no percussion students from the University of Toronto were in attendance. I say as usual because the percussion students at the University of Toronto by tradition don’t attend concerts, even Nexus concerts. I can’t imagine what keeps them away. They are missing opportunities to hear percussion repertoire currently being played throughout North America. As future educators and performers, one would naturally assume an interest, indeed a need, to expand their music minds. The habit carries through beyond graduation. Rarely does one see any Toronto percussionist at percussion music concerts.

However, Dan Morphy member of the Torq Percussion Quartet and one of Toronto’s best musicians did attend and we sat together. We hadn’t seen each other in quite some time and it was a pleasure sharing the concert experience with him.

The Steve Reich (b.1936) Mallet Quartet was written for Nexus and two other groups in 2009 and given its Canadian premiere in Koerner Hall by Nexus. I attended this performance and came away thinking about Picasso. Towards the end of his life Picasso would hand out favors to almost anyone. He’d scroll something on a restaurant napkin, sign Picasso, and the lucky recipient would go away feeling they’d just inherited a masterpiece. I wondered if Reich was up to the same game. Years ago, Nexus paid quite a bit of money to copy the music of a piece Steve was “writing for us”. This turned out to be Sextet, a work Nexus could never play again at least on the road because it required two extra musicians playing pianos and synthesizers. Now, the Mallet Quartet, a work instantly recognizable as being from the pen of Reich, but from all other points of view, a “toss–off”. A friend told me the middle section was “original”. Yes, but original does not equate with good. One does not always get what one pays for.

Nevertheless Ensemble 64.8 played the work with clarity and they’re set up, two marimbas at the back and two vibraphones facing each other at the front worked better in the music Gallery then it did for Nexus at Koerner Hall.

I’ll comment on only one more work, l. Hop (2) from Three Moves for Marimba (1998) by Paul Lansky (b. 1944) and performed by Kaylee Bonatakis. I liked this work. I asked Kaylee how long she’d been playing it because I thought she needed more time with it. Still, everything was there, and, propelled by an occasional bass note, the piece has an infectious swing.

After the concert I went to a pub with Ensemble 64.8, Dr. Palter’s sister, mother, father, aunt, and Dan Morphy. This made getting up the next morning a bit difficult, but I had to meet 64.8 for lunch. It was good to hang out with them in the relative quiet of a West Queen Street restaurant. One of the students is from Florida, another from Australia and the third from Fairbanks. Then, they were off to see The Avengers. They are staying around for the Friday and Saturday drumming event in Guelph and will fly home Sunday. I enjoyed their music. Keeping up with Morris is fun. From all indicators, he’s doing good things in Fairbanks, Alaska.

MUSIC APPRECIATION 101

Janis Joplin

I purchased PEARL in 1971. When I heard drummer Clark Pierson’s opening kicks and Ms. Joplin sing, “You say that its over baby, you say that its over now” I gulped and was willingly dragged into the magic that was her voice. Today whenever I hear the opening cut to PEARL I begin the smile in anticipation of a listening experience of the first water. Of course the original recording was pressed on LP and once in a while I still listen to this vinyl version, but dammit, CDs are more convenient. I own the so-called Legacy Edition. CD or vinyl, be sure to turn your volume to 11.

11 was one notch above her contemporary rock rivals. That’s the way Joplin seems to have lived her life and that is the way she sang, even in the most tender moments of Cry Baby. I can’t think of another song with such a cry or in A Woman Left Lonely, or in the hot Half Moon. She did have a great band, thank heavens for Full Tilt Boogie: Clark Pierson, drums; Ken Pearson, organ; John Till, guitar and Richard Bell, piano. I challenge anyone to name a better rendition of Me and Bobby McGee. It doesn’t exist, It can’t exist. And listen to Get it While You Can. She did. Admittedly, it cost her dearly, but I’ll be forever thankful for her commitment to every note. Her ability to express what she felt. Sometimes I’ve tried, but I drew a line Janis Joplin did not. At least her testament to emotional honesty remains for others, singers or not.

Jacques Loussier

Today I would not think of myself as a big jazz fan. I once was. For the 1st fourteen years of my life I listened to the original Dixieland Jazz Band, Sydney Bechet, Lizzy Miles, Bessie Smith, and Louis Armstrong’s Hot 5 and 7. Armstrong’s recording of W.C. Handy’s music and the great recording Anbassador Satch were favourites. What a band. Trummy Young on trombone, Arvell Shaw on bass, Barney Bigard on clarinet, Billy Kyle on piano and Barrett (“the fastest drummer in the world”) Deems on drums .

I then became interested in music with less formal structure. After college I played 12 years in symphony orchestras and reveled in the sound. In the 60s I listened to the Beatles (how many did not?) and Ravi Shankar. But jazz didn’t come back into my life again with any kind of seriousness until I hooked up with clarinetist Phil Nimmons, purchased a new release of his amazing early big-band compositions and did some improvising with him while I was in Nexus.

And then on my most recent trip to Germany, a friend of mine played a Jacques Loussier (b.1934) Play Bach Trio recording, bassist Pierre Michelot, percussionist Christian Ganos. Formed in 1959, they were together for 15 years and sold more than 6,000,000 recordings of Jazz based on the music of Bach before disbanding in 1974. I felt old. I graduated from high school in 1957 and it took me 55 years to discover them.

I’ve never liked arrangements of Bach’s music. Especially arrangements for marimba, glass harmonica, synthesizers, pop vocal groups, cats and dogs and, well, you get the idea. But Mr. Loussier is an artist of great sensitivity and taste, as well, he is in possession of a great technique, fluid and precise. Loussier, himself a composer, obviously understands Bach’s music. He does not use it as a vehicle for self-indulgence. His escapades never fail to convince me of his or Bach’s artistry.

During the last few weeks I have listened to this recording many times and it continues to delight. Bach was known as an improviser in the classical style. I think a concert of Bach and Loussier would have been a sell-out.

Posted by robinengelman on October 25, 2012 in Articles, Commentaries & Critiques, Composers, History

Tags: Jacques Loussier, Janiis Joplin